The title for this essay comes from Lennard Davis’s Bending Over Backwards (NYU Press, 2002), in which he argues that the academy consigns disability to “diversity's basement.”

This essay concerns my experience as a deaf spectrum professor and my efforts to receive accommodations.

This essay was rejected from history publications for being too right-wing. I’ve considered myself Liberal (at times, Radical) since my years in graduate school. Only recently have my ideas begun to sound “conservative” to others. I do not identify with any political party, and I have never done so.

The generally accepted convention is that Deaf—capital D--refers to a community of individuals who share a visually centered culture and the use of American Sign Language. Traditionally, deaf refers to the larger community of people who share the condition of not hearing. I used to self-identify as someone with a hearing impairment, but that term is no longer acceptable. Since I can hear, technically, I belong to the category hard-of-hearing (HOH or HH), but I find this designation does not do justice to the limited range of sounds I can hear. I self-identify as someone on the deaf spectrum (a term I adapted from the autism spectrum). I do not know sign language. I speech-read (formerly known as lip-reading) and use hearing aids.

deaf with a little “d”

My world is filled with sound, yet I cannot hear. Growing up, I could hear, or so I thought. Only in hindsight can I connect my high school reputation as an "airhead" to an inability to process words and sounds. In college, I gravitated toward the front row in lecture halls. In graduate school, a friend told me I might have a problem. The doctor said, "Concentrate. You must concentrate when people talk to you." So, I concentrated. I watched words form as they left a speaker's lips. I strained my ears to pick up every sound.

Oblivious to the conversations, announcements, questions, and answers concealed by decibels below seventy, I earned a Ph.D. in history, married, gave birth twice, and accepted a temporary full-time position at a major university. It is worth pointing out that according to American Community Survey (2008) data 1 out of 1,500 hearing people under the age of 45 earned a doctorate, while only 1 out of approximately 100,000 deaf people under the age of 45 successfully attained the same degree.

I successfully passed as "able-bodied," or so I thought.

I smiled, nodded, and murmured when I could only hear bits and pieces of a discussion, parts of words, or some voices but not others. A confrontation over my inability to grasp spoken language led me to make an appointment at the University's speech and hearing clinic. Here, I learned my hearing loss was congenital and degenerative. Still, no one, myself included, in my early years noticed how little I heard. The audiologist recommended two hearing aids. I opted for the most invisible model; I did not want people to think of me as Deaf. The hearing aids came with a thirty-day-full-refund trial period—my then-husband joked that the aids cost as much as a used car. Hearing aids are challenging and uncomfortable and do not "correct" your hearing like eyeglasses correct vision. Even wearing state-of-the-art hearing aids required me to work hard at deciphering speech.

Sound

I was unprepared for the world of sound. With the volume turned up, I heard the noise of the refrigerator, the dishwasher, and traffic—the daily hums tuned out by the able-bodied. Life after hearing aids changed me.

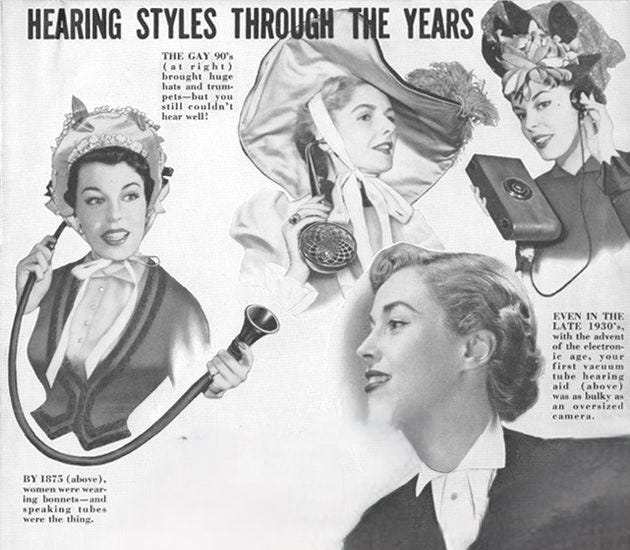

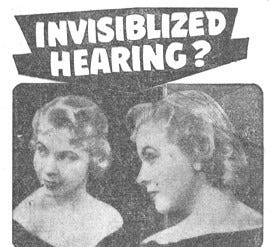

The first time I wore my new hearing aids in public, I made sure no one could see them buried in the canal of my ears. A Deaf woman approached me and began to sign. Mortified at being mistaken for someone disabled, I awkwardly extricated myself. The next day, I returned one of the hearing aids. The social stigma of wearing hearing aids is real. It is no accident that hearing aid advertisements often stress their “invisibility.” Some examples: Hearing Aids Can Be Ugly, or the series of ads from Phonak that make the “invisible” hearing aid sexy, or “Beyond the Stigma, Empowering Lives with Invisible Hearing Aids.” It is also worth reading Jaipreet Virdi-Dhesi’s “The Hearing Aid's Pursuit of Invisibility” in The Atlantic (August 4, 2016). The article argues that hearing aids have a history of shaming rather than helping the hard of hearing.

In my head, two hearing aids equaled disabled, and one meant a little trouble hearing. By the end of the semester, I returned to the clinic and re-ordered the second hearing aid. At thirty-three, I began a journey that would eventually lead to the path marked ADA (Americans with Disabilities Act).

Disabled with a big “D”

My temporary university position required me to continue my search for permanent employment. After several on-campus interviews failed to produce offers, I turned to a friend and colleague to vent my frustration.

"Gayle," she asked. "Do you inform the search committees about your disability? Do you return the Human Resources forms indicating you are a disabled job candidate?"

“I’m not disabled,” I responded.

“Gayle,” her voice growing firmer, “You are in your early thirties, you wear two hearing aids, and you have a lisp—some might call it a speech defect.”

I must have looked upset because she continued, “Because you hear differently, you speak differently. Maybe members of the search committees noticed something unusual or weird during your interviews. Not knowing about your disability, they don’t know what caused the odd behavior.”

Her words hurt and made sense. “Do you think I must tell my students about my hearing aids?” I could not yet call myself disabled.

“Yes,” she responded.

I followed some of her advice. I told search committees--only after being contacted for an on-campus interview. I never checked “disability” on any Human Resources equal opportunity forms. I wanted my colleagues and my students to connect with a history professor, not with someone on the deaf spectrum who happened to be a historian.

Wearing Shame

Having landed a tenure-track gender history position, I decided not to let my hearing impairment become an issue in scholarship, teaching, or service. The relative invisibility of my impairment made it reasonably easy to hide. I disguised myself as someone who could speak frankly, even laugh and joke at my hearing shortcomings. I feared burdening my colleagues or students with the responsibility of guaranteeing that I could hear them. Like many people who are not able-bodied, I created coping mechanisms. Asking people to repeat themselves more than twice usually elicited a “never mind,” “forget it,” or “it's not important.” Tolerating these silences stung.

I had to teach my children to bear with me when I asked them to repeat themselves. I told them it wasn’t fair to me when they refused to repeat themselves for the fifth time because it annoyed them. Given that the children of a person with an impairment can be impatient with accommodating a disability, we shouldn’t be surprised that young adult undergraduates are not always willing to take the extra step.

Like most Ph. D.s of my generation, my education prepared me to be a researching-writing historian, not a teaching historian. Making up for this omission, I immersed myself in pedagogical literature at a time when that meant going to the library and pulling the books and journals off the shelves. I did not consider myself a disabled professor-teacher and focused my searches on how to teach history well. Had I thought to check for articles or monographs on disability and teaching, the results would no doubt have emphasized teaching students with disabilities.

In the beginning, I rarely lectured. I spent significant time designing exercises to excite my students about history and limit my hearing requirements. I announce my impairment every semester, in every class, and on every syllabus. The language varies from semester to semester. Some years, I let loose my artistic side. I drew cartoons demonstrating hearing obstacles, such as a hand covering a mouth. Other syllabi attempt to give students a taste of not hearing (I hear “a maiden’s grave,” what is really being said?). Sometimes, I merely ask students to be kind and mindful that their professor can’t hear everything they say. The description of my hearing issues has varied little pre-ADA and post-ADA accommodations.

In addition to my plea for accommodations from students, I amplify my professor-who-is-cool-with-being-impaired schtick. Research shows that young people are more uncomfortable with the non-abled than they are with any other minority. The pressure to collect positive student evaluations means I downplay disability to increase student comfort. Over the years, sympathetic students have gossiped with me about some of the cruel things their peers in classes have said or done to make fun of my disability.

When I identify as someone on the deaf spectrum, I wonder if my students stop seeing Professor Fischer and categorize me as a disabled inferior someone who behaves “oddly” at times. I envy my non-impaired colleagues who can retain their professorial mystique. From day one, I bare my body’s shortcomings to rooms filled with twenty-somethings, virtual strangers. I am made vulnerable in these first meetings. Showing my hearing aids, Bluetooth streamer, and fancy microphone is a bold maneuver intended to foster a climate of acceptance and respect.A My classroom tactics bombed as often as they blossomed into inclusion or tolerance.

“Crip Time”

Generally, I don’t support overturning words intended to demean. Repurposing slurs into “positive” terms used only by and within the mocked group may seem empowering, but is it? I deliberately chose to use “crip time” because no other phrase captures how disability sucks time. In conversation, I seldom use crip for disability. When I say crip out loud, it is usually for its shock value. Words may not be violence, but they can hurt.

I’ve spent thousands of dollars and hundreds of hours trying to make my classes accessible to me. Those hundreds of hours are part of “crip time.” The non-impaired professor does not have to expend additional hours testing equipment or researching alternatives to conventional classroom practices such as discussions in circles. I cannot hear in a circle. The farther sound has to travel, the more likely it is that words will never complete the journey—discussion circles become games of telephone for me.

Frequently, I must invade a student’s personal space, placing my face inches from theirs in the hope that I can hear and comprehend what is being said. If students in my classes need to discuss material and ask questions, I need to figure out how to make this happen. My Bluetooth-enabled, multi-directional microphone picks up voices and bodies shifting in chairs and the conversation in the hall. It cannot determine what sounds are important and which are not. The Bluetooth connection picks up cell phone dings and pings even though I’ve asked the class to turn off their phones to limit electronic interference.

Putting on my professor costume—the one that projects the happy crip in Teflon armor— and wearing it on a four/four-teaching schedule is exhausting physically and psychically. Unlike some of my hearing colleagues, I cannot teach four classes two days a week. Teaching four classes two days a week leaves me incapable of using the other three days for prep or grading. I am that drained. A hearing professor might gain some empathy for my situation by imagining themselves teaching students who do not know much English. The professor with a rudimentary understanding of the students’ language must spend extra time preparing for class to succeed. The professor might write formal lectures, prepare answers to potential questions, or choose email with a translation app to connect to students outside the classroom. Would a hearing professor in such a situation feel worn out?

Again, crip time, for me, is all the additional time I need to prepare to teach successfully. Few colleagues or administrators grasp the concept of crip time, and it does not figure into my ADA accommodations. If I were to be released from teaching one class, that “free” time would be viewed as cheating or as a perk for being disabled.

Any deaf-spectrum professors are teaching here?

Although I received tenure and promotion to Associate Professor, I failed my first post-tenure review. I met with the then Provost to discuss why my file did not achieve the required standard. My teaching evaluations declined in the years since I became tenured. I explained that I taught one of the most challenging classes in our department—historiography—and that some students were unwilling to take a disabled professor seriously. On learning that I was not “officially” on the books as disabled, the Provost urged me to make an appointment with the ADA administrator in Human Resources. She also suggested that teaching online might be easier for me than teaching in the classroom. Submitting requests for accommodations to HR is challenging on several levels. I complete paperwork, and my audiologist completes paperwork verifying my impairment is authentic. Each accommodation application involves more form-filling. Legally, becoming a disabled employee did little to alter my life on campus—at first.B

Much later, I learned that some of my rights under ADA had been violated. Although I’ve never kept my disability a secret, when an employee shares information about a disability with Human Resources, that information is private. The then-provost infringed on my right to privacy by sending an email to various administrators and my chair announcing my name, my disability, and my accommodation. I felt grateful.

The ADA compliance officer and I toured all the classrooms in the building that houses my office. We decided that the least-worst of all the rooms would be where I would teach. The room had carpeting, was more square than rectangular, had one door in the rear, and was angled away from the main hallway. The only significant drawback was the bank of windows, which faced a busy parking lot. This classroom, my classroom, was the single accommodation the University supplied--until it didn’t. One semester post-ADA, my classes were scheduled in other classrooms. I was upset. I told my department chair that my ADA accommodation stipulated classroom ##. Turned out Human Resources had no record of me as legally disabled—back to the audiologist for more form-filling.

The (new?) computer program that assigned teaching spaces could not be set to give a specific room to a particular professor. However, if I reminded the chair that I wanted that classroom in the future, the chair would remind the dean, and the dean would make sure the room was assigned to me. I started getting emails letting me know I had been given ## as I desired. Was I supposed to be grateful? Did the dean and chair expect notes of thanks for doing me a favor? One of the many problems with accommodations is that they appear to benefit one individual’s body. Losing and regaining my lone accommodation transformed me.

nuisance with a little “n”

From a person who did not want her impairment to inconvenience anyone, I became a disheartened, depressed, and irate nuisance. I became the stereotype—the combative, angry, disabled professor. I spent many, many hours researching assistive-hearing devices and hunting for pedagogical articles and books written from the perspective of the impaired instructor—crip time. Predictably, most of the scholarship on teaching focused on best practices for instructing learners with disabilities. In fact, many of these books were already in my office. I relied on them to guide me when I fought for appropriate services for my child with a nonverbal learning disability and an autism spectrum diagnosis. As expected, educational assisted hearing devices were designed for the student to access the teacher’s speech. Few resources exist to aid the impaired professor.C

Teachers in K-12 work with parents, pupils, and other school personnel to write IEPs (Individualized Education Programs) or 504 plans. When schoolchildren move on to college, they seek accommodations from Disability Services (sometimes called Accessibility Services). The laws that protect students differ from those that protect faculty, who are employees.

ADA allows employers (universities) to claim that accommodating an impaired employee (professor) would cause an “undue burden.” For example, when the University where I teach moved to remote learning in Spring 2020 due to the COVID-19 scare, “Zoom” (a video-communications platform) became the primary means for meeting while apart. Although Zoom has closed-captioning capability, the process is cumbersome and works best with a third-party captioning service. First, I contacted Disability Services. I thought, “If I am having problems with Zoom, students must also be having issues. Maybe I can piggyback on whatever closed-captioning provision the Disability Services office has contracted.” Disability Services responded by letting me know that their office assisted the student population and that I needed to contact the ADA compliance officer in HR. In the end, the best the University could do for me, according to HR and IT, was to make transcripts available AFTER meetings wrapped up. Third-party live transcription services were too expensive and would be an “undue burden” for the University. After all, how many deaf-spectrum professors are here?

Can You Hear Me? Can You See Me?

When I became an employee with a legal disability, I was naïve. I believed that with ADA on my side, I would triumph over my impairment. I was not so naïve as to imagine ADA would “cure” me. I felt that I would be a normal professor in the classroom with the appropriate accommodations. Instead, I learned that the disabled are a problem, sometimes an expensive problem. And that, although society no longer locks away with impunity the blind, the crippled, the deaf and dumb, and the imbeciles, physical or mental impairments still offend the able-bodied. While classes met, I seldom bothered HR about accommodations—I became invisible. The amount of time it took to deal with HR plus the time class prep took made pursuing accommodations impossible. Between semesters, I pestered the office.

Making a simple phone call can make me anxious for days. I never knew if I would understand the speaker on the other end. I purchased a variety of amplifiers to use with my office landline. However, the acoustic feedback from my hearing aid receivers and the phone receivers overwhelmed my ability to hear voices. The few times I managed to align my hearing aid’s telecoil with a phone, it did not help enough to make conversing stress-free.

A closed-captioning phone, I convinced myself, was the answer. A year-and-a-half of bothering HR produced the phone. Six months later, the phone was set up, and I figured out the closed-captioning phone was worse than the old one.

My new phone number turned out to be two phone numbers. Anyone calling me had to dial the first number, wait until the electronic chords sounded, and then dial the second phone number. That is, if they could find either number in the first place. The University’s online directory provided nothing beyond a four-digit extension. Calling out required patience. The first number rings through to an operator—all operators are currently assisting others—who transcribes each caller’s speech, which appears on the display panel. Don’t get me started on the time lag, which is not unlike poorly dubbed foreign-language films. Obviously, this accommodation had to go. I no longer have a phone in my office, we make phone calls through the computer.

Crankier and Crabbier

I grow crankier and crabbier and more discouraged and contentious. Everywhere I turn, I feel alone. I belong to an oppressed minority, the largest minority in the world. And, yet, disability is seen as a personal problem or a medical problem—not a social justice issue. In 1976, the Union of the Physically Impaired Against Segregation asserted that disability is a form of “social oppression” that isolates and excludes those with physical impairments “from full participation in society.” I don’t know any physically-impaired colleagues at the University. There must be others who belong in this category. Who are they? Given that coming out as a disabled professor in higher education can damage a career, I wonder, are my coworkers hiding or passing successfully?

The physically impaired are a diverse minority encompassing a varied range of abilities, diagnoses, and identities. Student diversity, including the disabled, appears to be increasing on college campuses in the United States. Universities, including the one that employs me, seek to build a diverse faculty. I’ve learned the hard way that physically impaired professors are often an afterthought if they are thought of at all, in diversity and inclusion policies. Because disability is a protected legal category, top administrators and diversity officers see disability as a Human Resources problem and not a diversity issue.

I complained to the University’s acting Director of Diversity and Inclusion about my inability to access online meetings—something I considered an inclusion concern. She asked if I was aware of the ADA representative in HR.

To keep from crying, I joke with friends that I should be the University’s poster child for diversity. “The University should use me,” I tease, “to publicize that disability is a respected and accepted perspective here. Imagine the number of disabled students who would flock here knowing they would be valued members of our institution.” The disabled are a lot of work and cannot be easily pacified with virtue signals.

Disability as Diversity, Not Deficiency

I believe most institutionalized diversity programs give lip service to recognizing and valuing EVERYONE. Inclusion plans often use broad, inoffensive terms to delineate every person, such as “gender identity and expression,” “social class,” and, in case they missed an identity or two, “other important social dimensions.” Most institutions of higher learning invest a great deal of money to flaunt their commitment to diversity and inclusion. My experience as a disabled professor exposes the inherent insincerity of these promises. All identities are not valued equally.

I am not an advocate for identity politics. When I was in graduate school, women’s historians were turning away from the woman-as-oppressed ideology and looking for women’s agency. Ranking oppressions changed the United States.

I am disabled. Accommodations could make it easier to do my job. The process for obtaining those accommodations “victimizes” the disabled. The accommodation process should be a conversation—I learned this ten years after receiving my first accommodation. Since I am not an expert on educational audiology, I did not know what accommodations to ask for. This back-and-forth meant finding a possible solution, getting HR to sign off on the accommodation, trying it, and starting over again when it didn’t work. More crip time. It can take years to find accommodations that work. I’ve accepted the latest round of accommodations offered through HR and have no intention of continuing a conversation that dehumanizes me. It isn’t that my university has failed me, ADA failed.

Diversity really means race and ethnicity. Because diversity and inclusion are often a numbers game, I searched for statistics on disabled college faculty and diversity. The results are disappointing. Numerous public and private agencies document faculty (and student) diversity with obsessive detail. Most of these surveys exclude disability as a diversity category. Race and ethnicity dominate diversity statistics. About half of all lgbtq+ individuals with academic appointments hide their identity to avoid intimidation, making their numbers unavailable. Estimates suggest disabled faculty members account for around 4% of all tenured, tenure-track, and non-tenure-track positions. At the same time, 19% of all undergraduates reported having a disability.D

Given that race and ethnicity have become nearly synonymous with diversity and inclusion in higher ed, a substantial body of information exists chronicling the conditions that impact the presence of faculty of color. My intention is not to minimize the barriers faced by faculty of color. Nor do I want to play a game of one-upmanship or debate whether race trumps gender or gender trumps disability. Such diversions distract us. They keep us from noticing that publicly posted inclusion sentiments do not reflect the reality of our lives on campus.

ADA is supposed to protect my rights as a disabled employee. However, making ADA compliance the purview of Human Resources segregates disabled faculty. My primary identity is not disabled. If I have any hope of participating fully in the life of the University, I am required to prove I am disabled. Then, I must demand that the university remove the obstacles preventing my participation. A genuine commitment to inclusion would not force us to choose one identity.

Few academics would disagree that a diverse faculty provides positive role models for a diverse student body. Seeing educated, accomplished people who look like you is affirming. Don’t the nineteen percent of college undergraduates who self-identify as disabled deserve to see disabled faculty thrive in the classroom?

Feel-Good History/Feel-Good Stories

The Americans with Disabilities Act celebrated its thirtieth birthday. Pats on the back, champagne toasts, and long-winded speeches should acknowledge this milestone in the history of disability rights. As someone who never wanted to identify as impaired or disabled, I reacted to this significant event with mixed emotions. ADA provides me with the only weapon in my arsenal, frightening enough to get some accommodations. But to wield ADA, I must identify as disabled when I am so much more than disabled.

This is why I find diversity mandates troubling. They simplify complicated human identities to a single dominant category, resulting in divisions, not connections. Thus, identity politics reduced me to my group—I am disabled.

Allying diversity with inclusion suggests that colleges and universities want everyone to feel they belong. However, everyone is not given an equal voice. Some identities are more important than others. If a sincere belief in the benefits of a diverse student body, faculty, and upper administration was present, we wouldn’t need a diversity office.

I tend more to pessimism, with a dab of pollyannaishness thrown in, which may explain my mystification at the shortcomings of diversity offices. Each of my colleagues and all of my students brings unique life stories to campus. In class, at meetings, and at informal gatherings, we are exposed to people with vastly different life experiences.

Whether we realize it or not, we learn from one another. However, during the second decade of the twenty-first century, I’ve seen students who do not want to recognize as valid views that differ from their own—a troubling development. Favoring one or two categories of identification over all others makes me feel excluded and selfish or foolish for imagining my identities are valued.

Disability is NOT a Superpower

Stories about the “challenged,” the “handicapable,” the “differently-abled,” and those with “special needs” tend to be triumph-over-tragedy fictions that inspire readers or make them feel good. My ability to hear only thirty percent of what is said to me is not a tragedy. It is my reality. My growing bitterness is not a triumph, nor is it a failure. My story is simply a cry from diversity’s basement.

Notes

A. I now wear behind-the-ear hearing aids. These are the largest and most visible hearing aids. I made this choice for two reasons. First, my self-confident, impaired professor character would not be embarrassed by the hearing aids and would more likely show them off. In order to fully embrace the instructor I created, I needed the appropriate props or accessories. Curiously, when I asked my audiologist for behind the ear hearing aids in a bold color, I was told that those colors were only available for children’s hearing aids. Adult hearing aids come in hair colors—a sort of camouflage—to better hide the impairment. Second, behind the ear hearing aids are bigger— microphones, electronics, batteries, etc—and thus I hear better with more power working for me. In addition, I purchased a Bluetooth streaming device manufactured by my hearing aid company. The streamer is paired with a multi-directional microphone that feeds directly into my hearing aids. Concealed Hearing Devices.

Hearing aids differ, but their three main components are standard from aid to aid: a miniaturized microphone, a transmitter, and a receiver. Every hearing aid works on the same principle. There's a tiny microphone that picks up sound, transmits it to an amplifier which increases its loudness, and the receiver sends it into the ear mold. The result is a "gain" in decibels

B. Although I discuss teaching in the essay, the Provost had greated concern about my scholarly output. Before tenure, I published numerous articles and a book. After tenure, my research and writing time were consumed by a child with a mental illness and learning disabilities. Instead of scouring primary sources, I was reading best practices for dealing with my child’s disabilities, trying to find a psychiatrist who could accurately diagnose and treat my child, and looking for a lawyer to help me get my child into a school that could appropriately teach my child. In addition, during these years, I divorced and remarried. When I met with the Provost, I was 48 and pregnant and jumping through the hoops the public school system set up to keep my child in the district. My scholarly output was down. Advocating for a disabled child while being disabled myself made writing a feat that I did not have the strength for while also teaching a 4/4 course load.

C. William J. Peace notes that impaired faculty are often on their own in Audrey Williams June, “Indifference Towards Disabled Scholars, Especially at Conferences, Troubles a Disabilities Scholar,” Chronicle of Higher Education (June 16, 2014). Also see Peace’s blog, Bad Cripple. The University of Colorado, Denver, was one of the few higher education institutions with a page FOR disabled faculty. The limited number of resources on the page highlights how academia has largely ignored this minority. I found a few articles on deafness in the academy: Rebecca Raphael, “Academe Is Silent About Deaf Professors” Chronicle of Higher Education vol. 53, no. 4, September 15 2006, p. 56; James Crowder, “Can You Repeat the Question?” Chronicle of Higher Education, vol. 52, no. 38, May 26 2006, pp. C2–C3; Lissa Stapleton, “The Disabled Academy: The Experiences of Deaf Faculty at Predominantly Hearing Institutions,” The Chronicle of Higher Education published a special report, “Diversity in Academe: Disability on Campus,” (September 18, 2016). For those interested in disability history, a good place to start is the Disability History Museum

D. The various surveys were conducted between 2015 and 2019. I used the most up-to-date statistics I could find. See: Disability Statistics at Cornell University https://www.disabilitystatistics.org/; Institute of Education Sciences https://ies.ed.gov/ and https://ies.ed.gov/topics/postsecondary.asp; Higher Education Research Institute https://heri.ucla.edu/; ; National Center for College Students with Disabilities http://www.nccsdonline.org/; US Department of Labor https://www.dol.gov/odep/topics/DisabilityEmploymentStatistics.htm.